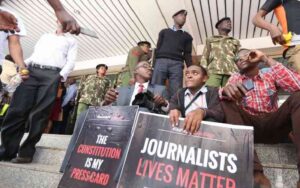

Silenced Voices: A Legacy of Impunity as Kenyan Police Officers Escape Justice

Impunity's long shadow persists over Kenyan journalists, leaving families without justice

Kenyan police officers accused of brutalising journalists are rarely brought to justice. The last two decades are stained by stories of officers getting away with crimes against journalists with near impunity. From the March 2023 brutal attacks on journalists covering demonstrations, or the severe beating of Nehemiah Okwemba and Reuben Ogachi by General Service Unit officers, to the high-profile fatal shooting of Pakistani TV journalist Arshad Sharif, in 2022 and the heinous murders of Francis Kaunda Nyaruri and John Kituyi in 2009 and 2015, investigations, where conducted, have often been insufficient to bring the responsible officers to justice

Our two-month investigation into more than 100 documented and media reported cases of police brutality against journalists revealed a troubling trend of poor or nonexistent investigations, even where there is undeniable evidence of such attacks having been captured on camera. Since 2015, only about one percent of journalists attacked by the police have been investigated, with little evidence of punitive action against the guilty.

The National Police Service (NPS), the Independent Policing and Oversight Authority (IPOA) and the Office of the Director of Public Prosecution (ODPP) stand accused of complicity in failing to bring rogue officers to justice.

Media rights advocates argue that the failures of these institutions to promptly and transparently investigate and prosecute those responsible for these attacks, is indicative of a systemic problem. These failures not only disregard Kenyans’ right to information but also suggest potential collusion between perpetrators and law enforcers. It undermines public confidence in institutions meant to curb police misconduct, they say.

“At best, this suggests a systemic problem leading to cases of attacks against journalists getting low priority attention, and at worst it suggests collusion between the perpetrators and the duty bearers” says Churchill Otieno, Executive Director, Eastern Africa Editors Society.

The Kenya Media Sector Working Group (KMSWG), an umbrella body of media rights actors, has repeatedly sought updates from IPOA, NPS and ODPP on investigations into police misconduct and brutal attacks on journalists. Several other human rights groups including individual journalists have separately written to these institutions seeking answers on the investigations or arraignment if any, in the cases involving police violence against journalists, but all have been met with persistent silence.

The lack of responses to inquiries and the slow pace of investigations not only discourage journalists from pursuing justice but also undermine press freedom. It not only demoralizes existing journalists but also deters new talents from joining a profession fraught with risks. This, combined with police failures to bring perpetrators to justice, creates a cycle of impunity.

“The cases have not received the seriousness they deserve from the arms of the criminal justice system. No wonder they hardly ever get to arraignment of the perpetrators.” says Otieno.

Mr. Otieno says it discourages new talent from joining the profession, makes journalists’ work harder than necessary, “but more important society suffers ultimately since in nearly every case where a journalist is attacked its often as part of a wider scheme to block ills from being reported to the public.”

Although media sector working group met with then-Inspector-General of Police Hilary Mutyambai and then-Director of Public Prosecutions Noordin Haji, both of whom confirmed their willingness and readiness to deal with offenders against journalists. The IG tasked his deputy in-charge of the Kenya Police Service, Njoroge Mbugua, who was helpful at some point during certain journalist attacks.

“However, not a single case has been resolved to my knowledge – in most cases it turns out the complainants dropped the charges” Otieno says, who is also the immediate former president for Kenya Editors Guild, a professional association of Kenyan media editors

However, journalists who spoke with us rejected claims that they abandon charges, citing that it is due to prolonged and often futile pursuit of justice.

Journalists allege that IPOA and NPS have been very economical with truth, allowing them to repeatedly claim that “investigations are still ongoing” even in cases that have lingered for years.

“I gave up following up on my case with IPOA after realising they were unwilling to investigate. They kept telling me that the investigations were still going on. It was exhausting after several months of pursuing my case,” said a journalist who is a victim of police abuse. He did not want to be named in this article for safety reasons.

In 2017, a joint media monitoring report “Not Worth the Risk” by Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 highlighted the police’s inadequate response to formal complaints from journalists.

“There is no evidence that any state actor has in the past five years been held accountable for threatening, intimidating, or physically attacking a journalist or blogger in Kenya” the report said then.

Families, victims, and media rights organizations, including journalists, want to press responsibility charges against the Inspector General (IG) of Police, the ODPP, and IPOA for failing to carry out their constitutional duties.

IG’s office is facing even more serious allegations of negligence and systematic cover-up of top police officials accused of killing journalists, Francis Kainda Nyaruri, in 2009 and Pakistani TV journalist Arshad Sharif in October 2022 at a roadblock checkpoint in Kiajiado County.

IPOA is also under the spotlight for making little to no progress in these and many other cases since November 2022, after fresh evidence on Nyaruri murder emerged.

The family of Pakistani journalist has since filed charges against IPOA and NPS in Kenya’s High Court On October 23. Arshad was brutally killed by police officers saying it had been a case of “mistaken identity”. He had fled his home country to Kenya to escape being arrested to face several charges, including sedition, for remarks he made on his show that the military found insulting.

But one emblematic case exposing these failures within the criminal justice system is the murder of Nyaruri in 2009. This case not only illustrates systemic failure to punish crimes against journalists but also symbolises poor investigations, cover-ups, intimidation, and death threats against journalists and investigating officers.

Nyaruri wrote for a privately owned Weekly Citizen under the pseudonym Mong’are Mokua.

Before his death he allegedly wrote a story accusing the then officer commanding police division (OCPD) Lawrence Njoroge Mwaura of using low-quality roofing material in building the Nyamira police station. His decomposing body was discovered on 29 January 2009 in Kodera forest, with his hands bound behind, and with visible wounds on his back, 13 days after he went missing on January 16.

Following a protracted six-year court case, in 2015, the case was finally dismissed for lack of evidence linking his two supposed murderers to the crime. Eight years after the judgment, shocking details of cover-up and failed investigations have emerged.

The unfolding details, which apparently were concealed from the court at that time, raise serious questions about the miscarriage of justice. The failure to interrogate key witnesses and suspects and the threats against investigating officers further highlight the systematic cover-up

Nyaruri’s family has formally written to the Inspector General of Police, IPOA, and ODPP, demanding a thorough review of both police and prosecution files in light of new damning details placing senior police officers at the heart of Nyaruri’s murder. The grounds for this review stem from the incriminatory disclosure that a taxi driver, Evans Mose Bosire, initially thought not to have provided a statement to the police, did, in fact, furnish a statement in the presence of Chief Inspector Peter Mwangi at Kisii Police Station on March 12, 2009. This statement implicated several individuals, including senior police officials. Meanwhile, despite the new evidence, IPOA’s progress has been minimal since the family wrote to them alongside NPS and ODPP on September 26, 2022.

In a document seen by our team, Mose detailed unsettling accounts of how he drove some people, including two police officers and Nyaruri, to a hotel the day he disappeared. Mose’s alleged confession is chilling and raises serious questions on why this piece of crucial evidence was kept away from the court, resulting in a miscarriage of justice.

According to the court documents, the investigating officers, Nicholas Mubeya and Julius Musoga arrested Mose days after he was found to be in possession of Nyaruri’s mobile phone. Mose and his girlfriend Teresia Nyaboke both used Nyaruri’s phone on the evening of January 16, 2009, the day he disappeared and again on January 18. Moses was then released from police custody without explanation and then disappeared.

In the statement, Mose said he picked up and drove three men – known only as Kafupi, Nyambati and Bosco – who are believed to be members of a criminal gang “sungusungu”, to the Zonic Hotel, located not far from the town of Kisii. The statement further said that when they arrived, Bosco made a phone call and two police officers emerged from the vicinity of Nyamira police station. The statement further alleges that the officers entered the hotel and then returned with a man who would later be identified as Nyaruri. The man was wearing a cap and holding two newspapers in his hand.

Mose said he drove the three alleged gang members, two police officers and Nyaruri in his Toyota Corolla (KAM 488K) to allegedly arrest another “thief”. Mose claimed that while in the car, Nyaruri was asked to identify himself by the men, which he did by producing an ID card and said that he was a journalist, and not a thief. In the statement, Mose further claimed that after Nyaruri identifying himself, Bosco ordered that he drive them back to Kisii town, where the two officers exited his cab.

Mose and the three men then drove through Nyakoe market, where they picked another person who owned a welding shop at the market. He then drove the four men with Nyaruri through various markets before stopping at a forest on orders of Kafupi and Nyambati.

Kafupi then pulled Nyaruri from the vehicle, holding his shirt firmly, and the four men disappeared into the thicket with Nyaruri as Mose waited in the car. Approximately ten minutes later, the four reappeared from the thicket, but without Nyaruri. The man they had picked at the Nyakoe market returned while wearing shoes, a jacket, and a cap that looked like the one Mose had seen Nyaruri wearing.

Mose went on to say that a week later, Nyambati – one of the four men – called him on phone to confess that indeed they killed Nyaruri and that they wanted him to take them back to the forest to burn Nyaruri’s body in acid.

At some stage during the court hearing, the investigating officers, Musoga and Mubeya, testified that they were threatened while investigating Nyaruri’s murder by then-Nyamira OCPD Lawrence Njoroge Mwaura.

Another officer, OCS Robert Natwoli, who was initially in charge of the case, was forced to relocate from Nyamira after allegedly receiving death threats from several police officers and members of the Sungusungu gang.

Lawyers who offered to assist the family to seek justice too were forced to flee from Nyamira due to credible threats and intimidation from then OCPD Nyamira. For Musoga, Mubeya and Natwoli, they abandoned the investigation and subsequently never appeared in court to testify again in the case.

In his September 2015 judgment in the Nyaruri case, Justice Hilary Kiplagat Chemitei raised serious questions about the failure to interrogate key witnesses and suspects named by the deceased’s family and other witnesses including the investigating officers.

Justice Chemitei raised urgent questions on the roles played by the OCPD Nyamira police station, Lawrence Njoroge Mwaura who had allegedly been adversely mentioned by witnesses as the one who had threatened Nyaruri.

The judge also questioned the role played by Evans Mose, who was a star witness and a taxi driver, who had been mentioned in the initial evidence by investigating officers Musoga and Mubeya and why his statement under inquiry never made it to court.

Two suspects, Japheth Mange’ere Nyainda and Winfred Nyambati Nyakundi were acquitted on 30 September 2015 after prosecution failed to connect them with the murder of Nyaruri – ending a six-year emotional rollercoaster without justice.

“In summary this was an extremely cruel and terrible death of a young reporter with such a young family. The matter was poorly investigated. Unfortunately, what they presented did not place the accused persons at the scene of crime or in any way connected to it. Perhaps the OCPD Nyamira then would have made his statement regarding the suspicion both by the deceased and his family, Justice Chemitei concluded.

“It was complete silence. Nobody was found guilty. There was no hope. It is like fighting the government,” Nyaruri’s widow told our team

Journalists and media rights groups have highlighted a troubling pattern, connecting incidents like the Nyaruri killing to violent attacks on journalists like Eric Isinta and Timon Abuna in March 2023 and the unsolved assault on Nehemiah Okwemba and Reuben Ogachi in April 2015. They draw a parallel to the emblematic case of John Kituyi’s murder in 2015, underscoring the disturbing similarities with the Nyaruri case. In both instances, deficient investigations led to their collapse in 2015 and 2018 respectively.

These voices emphasize systemic failures within the National Police Service, IPOA, and the ODPP. Despite inquiries, responses are elusive, met with either silence or the recurring statement that ‘investigations are ongoing,’ leaving many questions lingering. At the time of publishing this article IPOA and NPS had not responded to our questions forwarded to them

Mugambi Kiai, regional director for the freedom of expression organization, ARTICLE 19 Eastern Africa says it is concerning that little seems to come out of investigations. “IPOA should do more to hold the police accountable. Also journalists should push IPOA to share proactively information on the cases” he says.

This article was first published by the Standard newspaper here